foto by freepik.com

The manufacturer of your brand new, shiny, geeky smartphone promised that their fingerprint or face sensor is the gamechanger in digital security? Unhackable encryption? Great! But does the law provides you with the same confidence? Well, let's see...

Old laws in a brave new world

Every now and then we hear that judiciary comes across an issue which tests old laws in the new reality (see criminalfuture.com, a blog of my colleague Kamil Mamak). Some of them may seem a little bit sci-fi and are often deemed as pure academic abstract thinking. However, there are those that somewhat resemble traditional, analog and well-known problems but display them in a slightly different light. We like to call it a step-by-step adaptation of law. It is nothing revolutionary rather evolutionary. Stealing money from a bank is a crime regardless if they are paper bills or piece of code on bank servers. Property may be virtual etc. The subject of our deliberation changes parallel to the evolving technology and culture. That is rather obvious.

We think that the issue of using fingerprints (like Apple’s Touch ID) or facial recognition (Face ID) to access the encrypted content of your phone or computer (see generally

Efren Lemus,When Fingerprints Are Key: Reinstating Privacy to the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination in Light of Fingerprint Encryption in Smartphones, 70 SMU L. Rev. 533 (2017) who has done a great job showing the problem in the US perspective) arises as one of the best examples of a questionable step-by-step adaptation. Thus, it causes a little bit of disturbance in the force. Here is why.

Testimony v. surrender

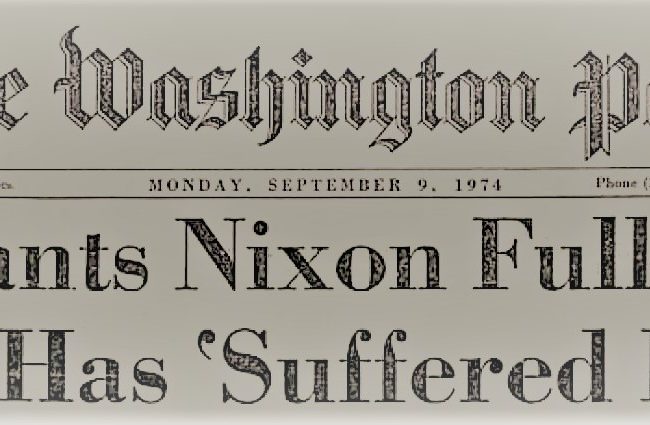

The prohibition against self-incrimination is one of the most paramount principles of civilized criminal procedures. It may be either explicitly provided in a constitution (or other supreme laws) like in the 5th Amendment to the US Constitution

(“No person (…) shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself”) or in a very general way like some other constitution of continental Europe or the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) in art. 6 provide - as a broad right to a fair trial. Those laws undergo interpretation, and until now it seems to be rather a consistent path of understanding the

nemo tenetur se ipsum accusare (“no one shall be forced to incriminate themselves”) principle to distinguish “testimony” from “surrendering.” As we may find in cases regarding providing information to law enforcement, both – US courts and the European Court of Human Rights, they tend to come to similar conclusions – one may not be forced to provide testimony regarding their potential criminal liability. It means that they may not be expected to be actively participating, in factfinding against them in the form of providing information. They may remain silent. That is the minimum standard (see application no 18731/91, John Murray v. the UK, application no 34720/97, Heaney and McGuinness v. the UK). Can they lie? “No” – according to the US law and “probably not, at least it is not the part of the right to fair trial” according to the European Court.

However, it looks totally different when a person is demanded to hand over some items, like documents, blood samples, voice samples or fingerprints. Here we are dealing with “surrendering” evidence which is not testimonial or communicative in nature, but exists in external reality. Nobody is thus compelled to disclose their knowledge or as once poetically stated “contents of their mind” (see i.a. Fisher v. the United States, 425 U.S. 391, 411 (1976), United States v. Dionisio, 410 U.S. 1, 7 (1973) , Doe v. the United States, 487 U.S. 201 (1988), Gilbert v. California, 388 U.S. 263, 266–67 (1967), Holt v. the United States, 218 U.S. 245, 252–53 (1910)). The same rationale has been accepted by the European Court investigating potential breaches of fair trial guarantees embodied in art. 6 of the Convention. In Saunders v The United Kingdom (Application no. 19187/91) the Court stated –

“The right not to incriminate oneself (…) does not extend to the use in criminal proceedings of material which may be obtained from the accused through the use of compulsory powers but which has an existence independent of the will of the suspect such as, inter alia, documents acquired pursuant to a warrant, breath, blood and urine samples and bodily tissue for the purpose of DNA testing.”.

So – where is the problem? - one may ask

It is all about the modern era and the digital revolution happening around. We become more and more “welded” to our mobile devices which contain a majority of important information we require to survive every day. Bank apps, calendars, all sorts of communication, photos, etc. are enclosed in a smartphone or even a smartwatch (see

David Chalmers TEDx Sydney Is your phone part of your mind? ). It has been raised that we even start to face

digital dementia which compromises some of our cognitive functions (mainly short-term memory). Moreover, the overwhelming nature of everyday functioning requires us to convey part of our knowledge to software. Provided that you treat your security and privacy seriously, you use at least 8-characters-random-passwords containing special characters, etc. Of course, a different password to a different service. It is rather obvious that you are not able to memorize all of that. Especially when, due to the growing need for encryption more and more simple apps or services require some sort of passcode. Considering all that, we tend to either use

“remember my password” function in our web browser as well as stream all passcodes to fingerprint or face recognition sensor. Can you imagine putting complicated at-least-8-characters passcode to your smartphone every time you want to interact with it? Then another time a different one for your bank and another for Facebook etc.? It is not a matter of laziness but simply of human limitations.

Why do the above matters?

Contrary to the European Court, the issue of compelling a person to provide a fingerprint to unlock a phone has been already tackled by the US courts. The result of which is rather an adaptation of the

“independent or external existence” doctrine providing that like blood sample or document, compelling someone to touch a sensor or look into a phone - does not violate the 5th Amendment. (see

Commonwealth v. Baust, 89 Va. Cir. 267, the United States v. Kirschner, 823 F. Supp. 2d 665, 669).

Can we adaptatively apply laws regarding physical key to Touch ID or Face ID? Isn’t there something significantly differentiating those ways of providing access to a secret? Fingerprinting traditionally in law has been a method of identifying a person and determining whether they were at a particular venue or touched something. Photography of one’s face serves the identical aim – identification of a person. Nowadays however they may bear much more functions, one of which is a biometric passcode. As

K. J. O’Brien stated

„people are born with fingers whereas physical keys exist independently of one’s body and require a separate acquisition. Fingers should not be physical master keys available to the government whenever it asks.” The issue becomes even more critical with one’s face. It is rather difficult to make it not available to others who may use it for infringing our privacy. Do you remember those movies when a villain pokes someone’s eye to use it to open a door guarded by a retina scanner? Not pretty, right? It seems reasonable to claim that nowadays fingerprints and face are equivalent to one’s memory. They are simply an extension of our capabilities to unlock things. Of course, because our thoughts are our most intimate and private value, it is impossible to take them away without our will. But considering the historical background of

nemo se ipsum principle, it all was aimed to protect us and our dignity from the ruthless violence of the government trying to control every piece of information. Now we are kind of forced to transplant part of our thoughts to the machine not because we like to do it (like writing a memoir) but we would simply cease functioning efficiently in the modern world when limiting the scope of our interactions with society.

That is why we think that there cannot be a simple adaptation of old laws to the modern issues in the above-described area. We see a clear-cut difference between thoughts and their substantivities. But the broader social context has brought us to a moment where they are mandatory not only an option. So, the argument against adaptation lays on a different level that it seems.

PS.

As a rather sad post scriptum, we feel obliged to present a secret option no. 3 where nothing actually remains protected. In an English case R v S (F) [2008] EWCA Crim 2177, [2009] 1 WLR 1489 it was elaborated that every passcode exists separately from one’s memory (it must have been copied to the computer in order to verify if it matches the password put in). But there is more to that – section 53 of Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (England) provides the following crime:

“A person to whom a section 49 notice (demand to provide a passcode to a computer – WZ. A.W.) has been given is guilty of an offense if he knowingly fails, in accordance with the notice, to make the disclosure required by virtue of the giving of the notice”. The penalties vary but may amount up to 5 years of imprisonment.

…