Last resort

Presidential power of pardon isn’t something unique even in modern republics. This genetically royal prerogative is vested in the hands of a country’s chief executive. It serves as a last resort when criminal law system has no other means of flexibility. I remain a little bit indifferent about that power as such, but what seems interesting is its scope, mainly considering the separation of powers or checks and balances principle. Many papers have been devoted to that topic (see historical outline presented in W.F. Duker, “The President’s Power to Pardon: A Constitutional History” William and Mary Law Review vo. 18, issue 3). Of course, depending on the country, the history and tradition of the pardon dispensing and its subsequent enforcement in criminal cases, may be very developed or just the opposite – not even worth mentioning. There are some general pardon’s-scope-related issues that attract the attention of scholars:

- Can a pardon be conditional?

- Does pardon require acceptance by its beneficiary?

- Can the president pardon himself?

- Must pardon be individual, or may it take the form of amnesty?

- Can a pardon be purely blanket in form?

- Must the president indicate the concrete crime he pardons from?

- Can the pardon be challenged before a court of law?

- Can a pardon be issued before conviction and cease the investigation (or even prevent it from being commenced in the first place)?

All of them has already been addressed in various publications, but the last two are somehow exceptional. Why do you ask? Well, mostly because they are only superficially related to the pardon as such. They actually perfectly reflect the unique complexity of the constitutional legal order of a state.

Just to clarify – I am not interested in criminal liability of a president for issuing a pardon and court’s (or other body’s) supervision over that. It is rather uncontroversial that in this perspective a president may be impeached for issuing pardons i.a. in exchange for bribes. That is a method of control over how they dispense their prerogatives and a sort of a safety anchor embedded in the system. But it is only a derivative matter.

Can it be reviewed?

The real question is the following – may the validity of a pardon be questioned? It actually combines the two issues I have emphasized – what happens if a pardon is granted before the investigation ends or during the first instance trial or during the appeal procedure? Would it be possible for the victim to question its effectiveness before the guilt is established by a proper and independent court of law in a due process?

I can bet that our immediate intuition is that pardon is an absolute prerogative and belongs solely to the president who is at full liberty to use it as he finds it fit. But should it be like that? What with a right to a fair trial, separation of powers and court’s exclusive right to administer justice? And what about the victim and their rights? If the president pardons someone before the establishment of the perpetrator’s guilt – does the victim inherently lose their right to demand justice? It was clearly stated in an old US case Burdick vs. the U.S. in 1915 (236 U.S. 79) where it was indicated that pardon carries an imputation of guilt and acceptance a confession of it.

Symbolism of pre-emptive pardon?

Criminal law despite it’s more and more technical appearance is all about condemnation and symbolism. Declaration “guilty” sends a twofold message – one to the society that criminal acts are punished and publicly declared as wrong, the second to the perpetrator that they should be ashamed by what they did and that the public identifies it as blameworthy. Pardoning after that declaration does not, however, vacate the verdict of history (despite what lawyers of ex-Sheriff Joe Arpaio tried to accomplish). The symbolic function of a criminal conviction is fulfilled regardless of the subsequent lack or alleviation of penalty. But what if we deprive the society (incl. the victim) of that symbolism? Can we call the beneficiary of the pardon a criminal, perpetrator, offender, etc.?

The above, let’s say purely academic doubts came to reality in Poland with an unexpected pardon of Mr. Mariusz Kamiński ex-chief of Anti Bribery Bureau (CBA). He was convicted to 3 years of deprivation of liberty for abuse of power as he had orchestrated illegal operations of the Bureau. Just after an appeal was lodged to the appellate court, president Andrzej Duda (his partisan colleague) pardoned him. It is important to know – before the appellate court decides about the appeal the conviction remains not final and the presumption of innocence still operates. The pardon formula was more or less “forgiveness and putting his acts into oblivion as well as discontinuing any pending criminal proceedings.” President added that he decided, in a way to release the administration of justice from that political case. Subsequently, Mr. Kamiński joined the new government as liaison officer supervising all intelligence service in the country. The appellate court indeed discontinued the proceedings due to the pardon which it had recognized as valid. But the casatory appeal was lodged to the Supreme Court that decided to hear the case in a broadened panel because of its specificity and uniqueness of the arising legal issue (I KZP 4/17). The question was narrowed down to one issue – can such pardon impact the ongoing criminal proceedings? The Supreme Court answered – no, it cannot. The court stressed that this presidential prerogative might be dispensed only towards individuals convicted in a final and valid ruling. Only such interpretation of Constitution in this aspect prevents from violation of other constitutional regulations of checks and balances. Thus, dispensing the pardon before the conviction is final and valid does not affect the ongoing procedure. It means that the appeal must be dealt with. The president may pardon a convict later on.

Constitution(s)

But as it was mentioned before – the devil is in the details. A big part of any debate over the scope of pardon in a particular system depends on the provision providing the prerogative in the first place. Let’s compare Polish an US constitutions to that extent.

Art. 139 Polish Constitution

The President of the Republic shall have the power of pardon. The power of pardon may not be extended to individuals convicted by the Tribunal of State.

Art. 2 sec. 2 US Constitution

The President shall (…) have the Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.

US constitution seems to be a little bit clearer narrowing the pardon only to offenses and their consequences. However, it was the judiciary that has provided that the power encompasses 5 types of clemency power: pardons, reprieves, commutations, amnesty and ability to remit fines and forfeitures (see K.H. Fowler, Limiting the Federal Pardon Power, Indiana Law Journal vol. 83 issue 4, p. 1652 Fn. 9). So obviously in some cases of dispensing of the power its validity or scope of it was challenged before the court. On the contrary, the reaction in the Polish case was almost hysterical on the part of president’s acolytes. Some of them (including lawyers) stated that the Supreme Court went beyond its authority and was not simple empowered to examine presidential pardon. Indirectly they refused to acknowledge the ruling as valid. Well, in a political heat – what can you do?

But the most interesting issue that actually arises from the unique case is the practical debate on the separation of powers. The system turns out to be more dynamic that one previously may have thought. The line of argumentation of Polish Supreme Court was naturally elaborated and long but the crucial matter focused on was the ultimate need for reading the Constitution as a whole. Especially interpreting particular competences of different branches in a broader context of the general political system provided for by the Constitution. One must mention the following:

- the system of government shall be based on the separation of and balance between the legislative, executive and judicial powers (art. 10)

- the organs of public authority shall function on the basis of, and within the limits of, the law (art. 7)

- the administration of justice shall be implemented by the Supreme Court, the common courts, administrative courts and military courts (art. 175)

- everyone shall have the right to a fair and public hearing of his case, without undue delay, before a competent, impartial and independent court (art. 45)

It is an imminent feature of the pardon to somehow interfere with the administration of justice (altering the outcome of the trial), but there must be a red line drawn crossing which means stepping beyond one’s authority. If the pardon is an absolute prerogative of the president which may be freely dispensed by them, it can be inherently followed by the notion to make the president the sole and supreme interpreter of that right. In case of the US Constitution, the outcome of such an approach still is limited to those 5 clemency powers. Ok, we may imagine another – the Arpaio issue – president pardoning someone and demanding the court files to be destroyed. In Poland because of the very general wording of the relevant provision the ambit of president’s invention is potentially very broad. The first thing that immediately pops into my mind is tax-exemption. President within his power to pardon declares that someone need not to pay an overdue tax. Very general clemency. The only counterargument that may be raised is that no one ever understood the prerogative in that way. Could the Ministry of Public Finance challenge that decision? I would like to see that.

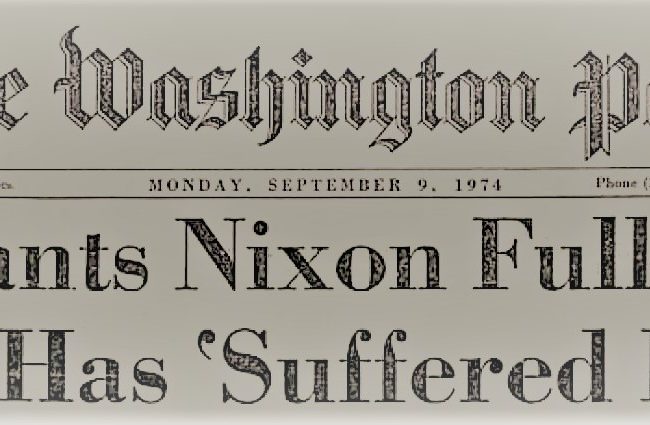

But going back to criminal liability. The decision of our Supreme Court was not aimed to limit president in his rights but in a way indicated the red line and stated clearly – “let the courts do their job. When they are done with a case – then you may alleviate the consequences”. It is however interesting if one reads the US Supreme Court decisions on the temporal aspect of pardon. In an old case – Ex Parte Garland from 1866 (71 U.S. (4 Wall.) it was explained that “The power thus conferred is unlimited, with the exception stated. It extends to every offense known to the law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken, or during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment. This power of the President is not subject to legislative control. Congress can neither limit the effect of his pardon nor exclude from its exercise any class of offenders. The benign prerogative of mercy reposed in him cannot be fettered by any legislative restrictions.” Surprisingly despite the Gerald R. Ford’s Proclamation 4311 regarding Richard Nixon, there were no significant court cases on the preemptive pardon. It is interesting what would be the current position of the Court? But what seems to be quite obvious – despite any reservations present in the Polish case – it would be obvious that the Supreme Court is authorized to examine the details of a pardon in its operation in the field of administration of justice.

Creature of laws with divine power?

We must remember that AD 2018 presidential pardon may not be seen as some kind of a divine right of a monarch, but a traditional prerogative of a chief executive but embedded in a strict constitutional context of rights and obligations of both – state and citizens. If we vest the administration of justice in independent courts, we exclusively empower them with the right to decide about the law and individual liability. One must not forget about the role of the victim which in different legal systems may vary, but it seems that the harmed party recently has become a significant figure in the criminal procedure. Another thing is the reasoning. Courts are obliged to provide the audience with their reasoning which may be later debated, evaluated and contribute to the evolution of legal culture. It is also a very basic obligation of the state to explain to the citizen why what happened to them. It is all about decency that has a very strong legal basis. How may we know that the decision of a public authority is not based on prejudice or some extralegal prerequisites? As Lord Acton once stated – “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

0

There are 0 comments